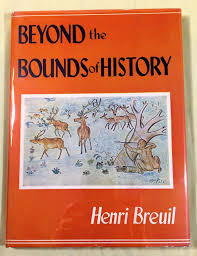

When I was young, I was fascinated by an old book called “Beyond the Bounds of History” which contained thirty-one (rather naïve) colour illustrations of the old stone age (Palaeolithic). It was a book, very much of its time, portraying groups of naked or almost naked cave people carrying activities of hunting, fishing and tool making. It also represented an image that people have held of the Palaeolithic, and in many respects continue to hold, that our ancestors were naked (if noble) savages.

When I was young, I was fascinated by an old book called “Beyond the Bounds of History” which contained thirty-one (rather naïve) colour illustrations of the old stone age (Palaeolithic). It was a book, very much of its time, portraying groups of naked or almost naked cave people carrying activities of hunting, fishing and tool making. It also represented an image that people have held of the Palaeolithic, and in many respects continue to hold, that our ancestors were naked (if noble) savages.

As an archaeologist, I learned that this popular image is in many ways flawed, particularly when it comes to the northern climes of Britain. So why has it emerged at all?

Some of it comes from colonial attitudes and the concept of “primitive” people, often described as “those who wear not the trouser”. An inherently ethnocentric view of the importance of clothes as a moderator of social behaviour, this was questioned and lampooned as early as the first half of the 18th century by writers such as Jonathon Swift. It’s persistence, however, comes from the biggest problem faced by those who wish to study humans that lived tens of thousands of years ago – lack of evidence.

Clothes tend to be organic materials and they very rarely survive in the archaeological record from any period, let alone the Palaeolithic. There are a few occasional finds of shoes, or shell adorned headwear, but no complete sets of clothes and no reliable illustrations.

So, if we are trying to tell the story of these first Lincolnshire people, we must also go “Beyond the bounds of History” and indulge in some informed speculation.

So, as the ice sheets retreat from North Lincolnshire and the first new arrivals begin to settle what might they have looked like?

Let us imagine that we have a family group. They live in a cold environment similar to arctic tundra, so wandering around almost naked is probably unwise. So, they would have been clothed and the majority of the clothing would have been animal skins, either with or without hair. We now have evidence that plant fibres were woven in the Palaeolithic, and we have evidence of plant fibres used as insulation in shoes. There is also a minute hint of pigment being used.

The most basic, and most universal article of clothing in the world is the breech cloth. This is usually a soft material, and I propose that Palaeolithic humans would have shared our view of that being a necessary quality to the garment. Doeskin is a soft, subtle material, although there are alternatives. The large number of scrapers in the Palaeolithic flint tool kit would suggest that defleshing skins was common activity, and de-furring them follows essentially the same process.

Shoes dating from the Palaeolithic have been found in Europe, usually a single piece of leather sewn up the back to form a heal and along the top of the foot to form a slip-on flat shoe. Stuffing the shoe with moss or grass made them resistant to cold, a technique still used today in Finland and northern Russia.

For leg coverings, we have less evidence. Otzi the iceman had fur leggings, but that was at a much later date. But the principle of wearing tube leggings tied to the waist is well established in many cultures and it may have been how our Palaeolithic man staved off the cold, possibly Palaeolithic woman as well. There is certainly no hard evidence of dressmaking.

The origin of the tunic is unknown, but simple tunics are very ancient. What form it took, how complex and with how much decoration is simply unknown. However, looking at ethnographic examples, you could envisage anything from simple poncho-like garments (as used by the tribes of the American plains) through to the highly tailored arctic parkers of the Inuit. Dear skin makes a good weather-resistant tunic. Longer tunics for women lead us to the idea of dresses, but they are not a natural human development. In cold climates, native peoples such as Inuit prefer the warmth of trousers. Perhaps, dare we say it, our Palaeolithic people had more than one set of clothes and chose what to wear depending upon the conditions or the occasion.

The final outer layer would be some sort of cape/cloak/wrap. This could be something like a warm bearskin in snowy weather or woven reeds to fend off the rain.

It is common to portray Palaeolithic men with beards and shoulder-length hair (it represents the stereotype of unkempt), but ethnography shows that hunter-gatherers go for short hair or shaven heads and clean-shaven faces. Hats seldom survive, but probably existed, and headdresses with shell adornment have been found on male skeletons from the period. Images of women, such as the Venus of Brassempouy (France), suggest that their hair was long and either styled in braids or held in a net.

So our Palaeolithic family has a man and woman dressed in skin and fur clothes from head to foot, and equipped to share the tasks of survival; hunting, gathering, providing food, shelter, heat and warmth. The children are smaller versions of their parents, their garments being simpler to allow for growth and the inevitable accidents of early life. It is likely that male and female children are not particularly distinguishable prior to puberty.

As caves are in short supply in Lincolnshire, they would have had to build some sort of shelter. Hides sewn together of a frame made from local wood would have shielded the family from the weather and a stone lamp would have elevated the air temperature to above freezing, even if the outside was much colder.

So we have our family of new arrivals, camped in southern Lincolnshire. Next time, I will talk about what they do all day.